The face was long – a marble slope that revealed nothing but strict judgment or, perhaps, brief consideration. The mouth - a thin, cold slash under the extensive, eagle-blade nose. The eyes suggested a bloodless cruelty – small and hard as black flint; backlit with terrible sadness; eyes that never looked sideways – instead the face would turn as a single weapon, casting wintery attention full strength. It was the face of a doomed centurion from one of Shakespeare’s histories, a choir boy aflame with too much faith, or a murderer.

If William S. Hart, the great silent-era cowboy, considered you trustworthy, you might see loyalty in that face – a sense of personal duty. If he didn’t trust you, he wanted to kill you. The eyes went squinty, glinting in blackness, and the face turned like a gun rotating on its turret. When those tiny pupils dilated like rangefinders, you might feel the whole world slipping away. If you were a man and laughed at him (the worst of all personal affronts), it would suddenly become clear in the horrible silence of his flat stare that you were in great danger. If you were a woman whose honor had been challenged, standing near Hart might make you feel safe. But no one, in the presence of Hart, every felt warmth.

Hart was born in Newburgh, New York in 1864 (or thereabouts) and had what biographers like to call a “nomadic youth.” By the time he had reached middle age, he had worked as a cowboy and dirt farmer, lived among the Indians of the Dakota Territory, and become friends with legendary lawman, Wyatt Earp. Hart had also enjoyed significant success in the theater (he was a Shakespearean actor on Broadway and played the part of Messala in the original stage company of Ben Hur). He was at least 45 years old when he made his first two-reel westerns for producer Thomas Ince in 1914. He was cast as the villain in both films: His Hour of Manhood and Jim Cameron’s Wife. By 1920, he had starred in a series of films, all westerns, often produced and directed by himself. He had become one of the top male actors in the world, an unlikely superstar. By 1925, however, the gin party that was the 1920s began to crave a bit more flamboyance from their cowboys, and Tom Mix came riding over the range in white, clean outfits; wearing his dazzling smile like an expensive accessory. Hart solemnly packed his saddle bags and retired to his ranch.

William S. Hart is fading fast from public memory, as are all the great silent performers who first brought Americans into the theaters. In another generation, he may be a half-understood myth – a name that only sounds familiar. Yet his work defined forever the archetype of the Western Cowboy. He was the first silent, hard man; the first grim loner; the stoic patriarch of a lineage that follows a direct path to Gary Cooper, Randolph Scott, and Clint Eastwood. Yet, as with most fine things, time has diluted the purity of the original. Cooper was tall and chivalrous as Hart, but he was too beautiful, gave his lopsided grin too easily to the girls. Randolph Scott would be the favorite son, all angles and hard leather (and both Hart and Scott became western heroes at middle age), but for all the power of Scott’s lined, granite face; the eyes held the occasional twinkle of mischief, a playful heart under the hardened minerals.

As for Eastwood, he inherits much from Hart, particularly in glorious twilight. William Munny (The Unforgiven 1992) is a part Hart might have played, yet a William S. Hart character would not have failed as a pig farmer and would have never needed to fuel his devils with liquor in any case. Clint Eastwood is often a good man fighting away the evil man in himself. With Hart it was the opposite: Hart struggled to purge his few angels so that he could get down to business. The Hart cowboy was not good, was often a thief or killer, but might find moments of goodness (or not) in the course of a film. Indeed, he was known as “the good bad man.” In recent years the screen has favored only bad good men.

The Hart cowboy had no friends, had no wife, had no humorous sidekicks. In fact, Hart never seemed to like his fellow humans with all their weak, pathetic habits. He often did things for the honor of women, but seldom, if ever, for love of a woman. In the end, always, he could live without them. His characters, though often bank robbers or murders, never drank or smoked, never visited a whorehouse – never gambled or played the harmonica around the evening campfire. All these pursuits suggested a need for pleasure or companionship– a contemptible weakness. If William Hart went into a bar, he was looking for someone he wanted to kill or question. He was always a man on a mission, moving from point A to B. Vice, or any pleasure, simply got in the way – blocked his line of vision.

Hart invented a gritty, realistic style of Western. He was zealous in his love of the West and insisted on authenticity and perfect detail. When a saloon caught fire in a William S. Hart movie, entire, full-scale town sets were put aflame and allowed to blaze to ashes (Hell’s Hinges 1917) because that was how it happened in the real West. Actors in such a Hart movie often had to speak their silent lines blinking and shielding their faces from the heat waves. In the West of William Hart, wooden buildings look aged and forlorn into a fur of soft grays. Saloons are small and bare, and the characters milling around inside them look desperate and starved. Town streets are littered with chickens and pigs. Townsfolk are always blighted by poverty; women and men alike dress in drab rags, blink up at the brutal sun. The men are always filthy and seem at times simply of the filth (in one of the opening scenes of 1921’s Tumbleweeds, the camera shows us a huge sow, sprawled happily in the street up to her snout in a pit of shit and mud – cut to a shot of a man lying in a fetal position on a table in a saloon, snoring and sputtering in unconsciousness after a night of high times. Any questions?). Hart rides through these towns, the hooves of his horse sloshing through the mire, his face set forward; looking forever toward the thing, whatever it is, he must do.

How does one so humorless, so cold – so completely without human need - become the first Western hero?

Hart’s last great film, Tumbleweeds (1925), is about the great land rush of the Cherokee Strip of 1889. It is (in true Hart fashion) a shockingly realistic film about the sort of atrocities that occurred when that huge strip of land in Oklahoma was simply offered on a first-come-first-served basis. Hart plays Don Carver, a drifting cowboy (a tumbleweed) who sees his way of life vanishing. In one scene, Hart’s horse is startled by a rattlesnake. Hart instinctively pulls his revolver, but stops himself as he gazes down at the rattling serpent. He holsters his shooter. “Go ahead and live,” he says (via title cards). “You got a whole lot more right here than them that’s a comin’.”

As the movie progresses, things don’t go Don Carver’s way. After one particularly unpleasant afternoon, Hart is again riding along a horse path and the same viper spooks his horse. This time Hart’s eyes flash, the revolver is suddenly at the end of his hand, and he blasts the snake’s head off (as always Hart’s commitment to authenticity is impressive).

“You didn’t use good sense, meetin’ up with me today,” he says over the snakes headless carcass.

Hart never gave away his thoughts. That is to say, his motives weren’t obvious, and his actions were often terrible and unforeseen. Then as now, that makes for a fascinating character. A whole generation of movie lovers couldn’t wait to see what he would do next.

*****

Mykal also wrote this in our conversation about William S. Hart and gave me permission to post it:

I have seen most everything by Hart, but sadly his best movie "Hell's Hinges" is out of print. I saw it years ago in a film class, and he (Hart) really impressed me so much I became a lifelong fan. I can still remember the professor grinning while watching the movie at a moment when someone in a bar cracked a funny at William Hart's expense. Even through the silent film and all the years, you could feel the bar on screen become still as Hart gave the fellow his full attention, the full force of his terrible face. The classroom became equally still with only the clattering of the projector (back in those days, real 35 millimeter film and real projectors).

"No one ever laughed at Bill Hart," said the professor quietly. So true.

***

To visit the guest blog archives, click here.

If you're interested in doing a guest blog post, you can e-mail me at silentsandtalkies103@yahoo.com.

13 comments:

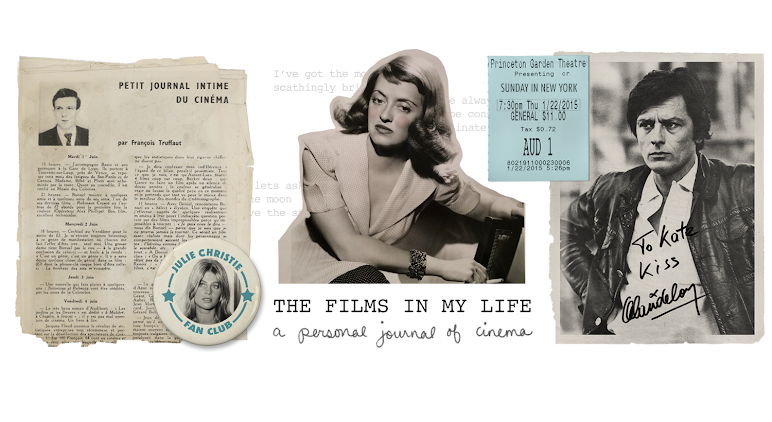

very, very good and a really fantastic painting!

An excellent analysis on Hart's career and screen persona. Really very well done. Brooding portrait goes nicely with it.

Kate: It is a thrill to see your portrait of Hart next to my guest post. As always, you have your subject nailed. Thank you for the guest spot on your wonderful blog -- Mykal Banta

Fantastic post! You made a very excellent essay on him, Radiation Cinema! And the sketch is a perfect likeness!

I see you've added me to the list Kate - looking forward to it!

Thank you so much for that post, Mykal. Sadly, I think you are right. Eventually William Hart may be half forgotten That is a shame as the Western owes so much to him. The one thing I find remarkable about Hart's films (which cannot be said of other Westerns, both of his time and more recently) is that they hold up so will. Tumbleweeds is as powerful today as it was in the Twenties.

Thanks for dropping by Art Of The City. I love what you're doing on here - the drawings are really stylish and you've got some really interesting articles up on here. If ever you are stuck for a guest blogger, give me a shout and it'd be a pleasure to write something - there's a few actors I'd like to see you turn your pen to!

Hell's Hinges (1916) is not out of print. It is on the (admittedly expensive) Treasures from the American Archives DVD set.

Silentfilm: Thanks for the tip. I was not aware it was still available as part of a collection. I have already placed my order via Amazon for the Treasures set (I would have paid double for that collection!).

I couldn't agree more about Tumbleweeds holding up. Still a thrilling piece of film making. -- Mykal

Mercurie: I couldn't agree with you more about Tumbleweeds holding up well. As you say, so few films do. Tumbleweeds still packs a punch over 80 years after its release. I wish Hell's Hinges could be had in a more affordable way, so that more folks would see it. I have not seen it myself in years, but will very soon (see above comment). I remember it as being simply brutal and completely (obviously) unforgettable. -- Mykal

Hart's The Toll Gate (1920) used to be available on DVD from David Shepard and Image Entertainment. You should be able to find some used copies.

I have 16mm prints of a couple of his films, including his feature The Return of Draw Egan.

Silent: I have the Image entertainment DVD edition of The Toll Gate. Draw Egan I have seen on a VHS edition I have that is so old it no longer plays very well. I am very exceited about Hell's Hinges and thank you again for the info. -- Mykal

Thanks again Mykal for an outstanding post!! Can't wait to read the Douglas Fairbanks Jr. one you have lined up for June :)

SP- I'd love to have you do a guest post -- who do you have in mind?

Post a Comment